Guest Program 2: here/where

Saturday, 26.03.2022, 20:15 @ BLICKLE KINO – Belvedere 21

This program is presenting a selection of films that contrast the ideas of a home, of a place to be and to remain still – with the concepts of movements and the motion to drive.

Simultaneously, the repetitive quality of human activities – may it be in an idle state, lingering, staying here, or may it be in going somewhere, being on the road, traveling – is expressed through varying approaches. The circular characteristic of recurring exercises appears as a core element of human activities.

Curated by Holger Lang. (Approx. 90 min)

Remade: Hans Scheugls „Wien 17, Schumanngasse“

Karl Wratschko | 3:00 min | 2021 | AT

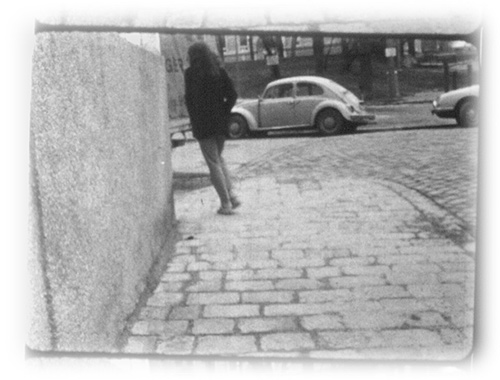

Over half a century has passed between the two films. In January 1967, Hans Scheugl shot his first independent work, Wien 17, Schumanngasse: a phantom ride of barely three minutes in which the beginning and end of the street also mark the beginning and end of the film. In January 2020, Karl Wratschko produced a “remake”: the same street, the same duration, and the same format, 16mm, black and white, no sound. Remade: Hans Scheugl’s “Wien 17, Schumanngasse” is less of an artistic appropriation than an homage, a revisiting of a classic of the Viennese avant-garde. In contrast to the usual practice in commercial film, this remake is intended to neither outdo nor supersede its predecessor, but rather to bring it back to life, and back to the screen with a stronger presence.

On the one hand, film history is not a one-way street; on the other hand, the street named after German composer Robert Schumann in 1894, two years before his death, actually now is. This is one of the changes that are most noticeable when viewing the two films one after the other or, even better, in parallel as a double projection. Most of the vacant lots along the drive, starting at the Währinger Gürtel and ending in front of the footbridge leading to Gersthofer Straße, have now been built over; parked cars dominate the streetscape; and there are even fewer people on the road now than back in 1967.

The unspectacular ordinariness of Schumanngasse recedes into the background compared to the deliberate speed taken on the one and a half kilometer route heading out of town. There are no traffic lights, but the eleven cross streets turn both the old and new versions of the film into a nerve-racking action sequence. The driving time, shooting time, and presentation time are all identical. Only with the final image, the film’s signature, does Remade: Hans Scheugl’s “Vienna 17, Schumanngasse” cleverly permit itself to diverge from the original: it ends with a street sign from the beginning of the one-way street – “Vienna 18, Schumanngasse”. (Michael Omasta, Translation: John Wojtowicz)

Sa, 29. Juni / Arctic Circle

Gustav Deutsch | 3:00 min | 1990 | AT

Two married couple on a journey from Vienna to the North Cape and back. On Saturday, 29th of June they cross the polar circle and stop by the sign which says “Arctic Circle”….. (Gustav Deutsch)

DONALD JUDD and I

Sasha Pirker | 3:30 min | 2016 | AT

The title of the film indicates a relationship, or what is more, trust and intimacy: “Donald Judd and I” is like something said in passing and only up close. But in fact and from the very start, Sasha Pirker´s four-minute miniature DONALD JUDD and I encapsulates manifold relationships and shifting dynamics.

In terms of narrative appearances, at first the “I” of the title is attributed to a female voice off-screen. It belongs to Marianne Stockebrand. The woman who became Judd´s life-long companion is heard recalling their common visit to the Schindler House at King´s Road in Los Angeles in 1988 – or maybe it was 1989? Meanwhile, the camera maps out an entirely other (contemporary) space flooded with light via static and initially, intensely fragmented shots. It is the Whyte Building on Oak Street in Marfa, Texas – part of the Chinati Foundation Judd established and Stockebrand managed many years following his death. The room in LA is reimagined, where Donald Judd discovered Schindlers furniture and quickly struck a bargain for the production of a complete set. The memory of that place is as if superimposed upon the room we see on screen, in which the idiosyncratically angular furniture of the Austrian architect now embarks on entirely new relations with early paintings by the minimalist artist. The presumably “exclusive” relationship between Donald Judd and “I” consequently opens into a multi-faceted dialogue, naturally including Sasha Pirker. Last but not least, DONALD JUDD and I tells of a filmmaker’s encounter with an (art)historically loaded location, it is a “small story” woven of individual narrative threads that ultimately merge in a single space. (Esther Buss)

Stunden Minuten Tage

Edith Stauber | 9:00 min | 2017 | AT

A day in the life of a woman. She is only to be seen in excerpts.

What is important is not the woman as an observer, but rather what is to be observed: the everyday images and sounds. Put together like Lego blocks, a poetic density emerges, a rhythmic soundimage.

TOUTES DIRECTIONS

Billy Roisz, Dieter Kovačič | 13:23 min | 2017 | AT

The beginning: a camera lens that gazes downward, tight against the street as though along the groove on a record. The camera as sound head, scanning the world rather than recording it, generating sounds from the structures of the landscapes passing by: a consistent gliding along the nearly flawless asphalt turns into an LP´s soft sizzling, hissing, static; speeding up the trip generates cacophonies, at times even melodies, which coincide with every new structure of the world in front of the sound head, to then fit together again to something beyond mere noise. This work contemplates the moving image – in a close association with the avant-garde of the 1920s – as visual music, more precisely: as music that originates in the visual, produces itself from the visual. In contrast to most works by the two, it is not abstract forms but streets and landscapes that dominate the image; shine through relatively clearly, to then pass over into the abstraction of the sound world. In this way, the picture becomes a sound space (generated by the two artists in collaboration with the trio Radian) in which rhythm, timbre, and noise connect along the horizon to a timeline. “All directions,” as the title states, describes both the movements of the image (along the world, into the pictorial depth, upward in treetops rushing by, and downward, gazing at the crumbling patina of the country road) as well as an aesthetic experience, which is presented by the visual as music, the acoustic as motion picture, and the real world as abstract pattern. A thirteen-minute road movie into the night in which real things blur in order to appear as pure form, pure movement, pure light, and pure sound. (Alejandro Bachmann)

Wien 17, Schumanngasse

Hans Scheugl | 3:00 min | 1967 | AT

A car drives through Schumann street from its beginning to its end and is filmed in such a way, that the beginning of the film is exposed exactly at the moment the car starts at the beginning of Schumann street, until at the farthest end of Schumann street the camera is just able to take in the street sign. The drive was filmed in one take, end and beginning of the film being identical with the end and the beginning of the street. A regular roll of 16mm film has a length of only 30 m, so if Scheugl wants to film Schumann street in one take from beginning to end, he may use only 2 and 3/4 of a minute, because these 2 and 3/4 of a minute are the equivalent of the 30 m at a projection speed of 24 frames per second. Scheugl is thus forced to consider the time of the film take and to regulate the speed of the car. The length of the street and the length of the film strip become identical by an apparent equation: space becomes time, space distance becomes time distance/duration. The words “the duration of the film is identical with the duration of the drive through Schumann street, but the length of the street is not identical with the length of the film strip” overlook, that time and space are reflective, and mis-understand what is demonstrated in Wien 17, Schuhmanngasse, the relativity of the reality of experience. Our sensual organs provide a daily film, whose rules may be made conscious by this film. We will never know, how long this street really is, since rules and structures of reality are only gaugeable by the rules and structures of our image forming calculations, thereby never examinable. (Peter Weibel)

carte noire

Michaela Grill | 2:30 min | 2014 | AT

White flashes in the dark of the night. As though etched out, dabbed in. Flickering specters, ghostly visions. A veritable phantom ride, a film of tension.

In carte noire, Michaela Grill’s sinister road movie miniature, she continues her cinematic movement from an object’s abstraction to its alienation. She now arrives at a classical, and highly charged motif from popular culture and cinema: the lonely car ride on an empty road through the countryside, which more or less automatically sets off trans-genre associations. Not only at the surprising end, one can assume that hinted at here, among other things, is a “lost highway,” based loosely on David Lynch. The film is based on a subjective, straight ahead shot, with a view of the asphalt strip of road including the middle stripe. First it disappears behind a knoll, then surfaces again and leads to the next hill. One seems to make out a sparse steppe landscape on the sides, a gently rising mountain on the horizon. The digital processing has turned it into a negative image in flickering black-and-white, like oil pastels on dark board. It is a scarce two-and-a-half minute fragment of a nocturnal drive on precarious terrain, endowed with a quivering, uncanny sound by Andreas Berger. The asphalt vibrates and the horizon lightens. The motor rattles and view blurs. An imaginary trip. Film noir. carte noire. Based loosely on David Byrne, we’re on the road to nowhere. The little owl is waiting. (Isabella Reicher)

The French Road, Detroit MI

Arthur Summereder | 7:00 min | 2016 | AT

Transpiring in the dark night of a city later identified as Detroit, Michigan, this conversation serves as a kind of establishing shot introducing the theme of Arthur Summereder´s The French Road: illegal auto races held at night on regular public streets. The darkness that perfectly obscures these races simultaneously indicates problematics of representation: How do you represent a ritual, a culture, a community that firstly does not want to be shown, and secondly, is not your own – a world briefly encountered that remains foreign. How to show something without falling into the trap of an exoticising gaze? To this end the artistic intervention that provides the context remains offscreen: the city, location and protagonists are present, but are never seen. This dialogue in the dark makes it clear the filmmaker can only represent an intruder – “I´m givin´ you a warning, man. This is Detroit,” – and is followed by a shot that is both concrete and abstract. It shows the surface of a vertically tilted street covered with marks revealing various forms of use inscribed over the course of time: tire tracks and black rubber abrasions, white road markings, manhole covers and strips of tar used to repair ruptures in the asphalt. This geology of the road surface unexpectedly exhibits signs of the socio-economic and historical context: The street in The French Road is far off the beaten track of the road movie and counter-cultural mythology, serving both as expression and impression of a city that rose and declined together with the auto industry, ironically no longer capable of affording to maintain its infrastructure. What remains is atmospheric: the sounds of starting motors, screeching tires, a police siren and the chirping of crickets in the Summer night. (Claudia Slanar)

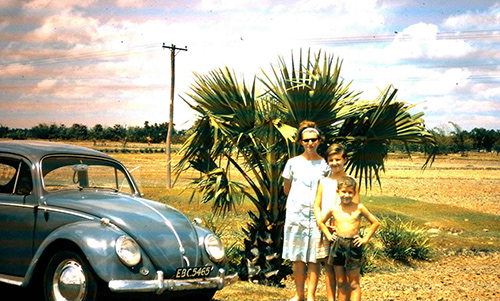

Zuhause ist kein Ort

Clara Trischler | 14:25 min | 2015 | AT

With Home Is Not A Place, Clara Trischler creates an audiovisual collage gleaned from fragments of her family’s history. Narrated memories are combined with filmic snapshots from the family’s private archive. Looking back in time, the filmmaker’s grandparents report to her about stages of life and particular crossroads. The framework introduced at the outset of the film serves to contextualize these elements and resembles a scrapbook of memories. Biographical scenes are recalled according to a linear pattern, telling about life together in former Czechoslovakia, subsequent work-related trips to East Pakistan and Kenya. So it comes to pass that this Slovakian nuclear family is on the road when the Prague Spring breaks out. They experience the upheaval from a distance and decide not to return home – they want to provide their growing children the possibility of a more autonomous life and individual freedom. Their flight is accompanied by the unease of leaving family members back home for an indefinite amount of time. This painstaking portrait of Trischler´s grandparents additionally outlines an understanding of the roles played within familial structure. But above all, Home Is Not A Place tells about lives shaped both by uncontrollable forces and self-determination, and about the fundamental human need for individual freedom. (Jana Koch)

fenster / drei sätze

Martin Bruch | 12:00 min | 2006 | AT

The view out the window: in the foreground, the changing objects that document the passage of time and changing of years, the empty construction site along the row of houses on the street across the way to Schönbrunnerstrasse, the moving crane, the house that is being built, the birds, clouds, weather, the atmosphere created by the light, in combination with the noises from inside and outside the room, with an open or closed window depending on the season. The film tells of the desire to get up, bend over the ledge or roll out onto an imaginary balcony to watch what is going on in the courtyard. For ten years I occupied this fourth story apartment on Margaretenstraße, carefully planned and equipped for a wheelchair, but was seldom home. I did not think much about the amazing view over/in the yard until my retirement, which coincided with the completion of the film handbikemovie, which changed my everyday life. (Martin Bruch)

Gertrude Stein hätte Chaplin gerne in einem Film gesehen, in dem dieser nichts anderes zu tun hätte, als eine Straße entlang und dann um eine Ecke zu gehen, darauf die nächste Ecke zu umwandern usw. von Ecke zu Ecke.

Ernst Schmidt jr. | 3:00 min | 1979 | AT

A reconstruction of the “concept film,” which Gertrude Stein (“a rose is a rose is a rose”) suggested to Charlie Chaplin in the 1920s. (E.S.jr.)

(This film is part of Schmidt´s 20 Action and Destruction Films.)

Actress: Brigitte Kowanz

Antoni Schumann Circle

Holger Lang | 13:30 min | 2021 | AT

The question: “What to do with your time?” appears to be one of the most fundamental issues conscious minds must tackle. However, the less prominent questions about the “where and when” of what a person could be doing seem less contemplated and less concerned. When considering a moment in a person’s life, it also always requires considering a specific location and a point in time related to the interval that this person has already lived. The passing of time can be observed standing still, silently and in waiting, or it can be experienced in movements that allow the viewers to feel like they are passing by while the world is standing still. Nevertheless, time is passing, and the attempt to sequence this experience is the only thing the human mind has figured out to do with this sensation. In the end, it does not matter where you go, as long as something keeps moving. You could also sit on a motorcycle and drive around the same block of streets in any city on this planet, again and again, in circles. Or you could do this exactly 20.000 days after someone else was doing the same thing.